The wind of change is blowing in Myanmar. The country is slowly opening up and recently ‘more’ democratic elections were held. Many Myanmar women have expressed their desire to be educated to be part of pivotal times in Myanmar history. According to them, without education they are pushed back into traditional roles, without skills, knowledge and confidence to become influential stakeholders. And what the women argue for seems logical; studies have shown how education is a powerful tool to change women’s position in society. It seems a straightforward solution to problems marginalised women from Myanmar are faced with, but due to a complex web of economic, social, cultural and political factors, fierce educational reforms are needed before education can function as a vehicle of empowerment for women.

In general, Myanmar women are hardly seen and heard in shaping the present and near future. Women’s participation on the labour market is only 48.4%, compared to the 81.9% for men, they are overrepresented in low skilled work and get paid less than men. Also, in politics; only 6% of the parliamentary seats are taken by women, they are poorly represented at all Myanmar’s subnational governments and they have little knowledge of the discussions taking place in their name at political level. Due to the lack of women in influential positions, contextual issues behind gender relations and women’s marginalisation are not addressed in substantial ways.

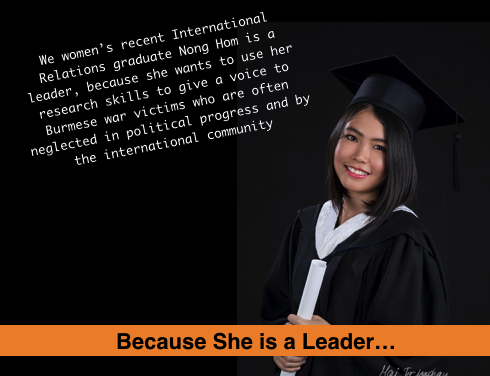

For Nong Hom -one of the students We women foundation has supported, several qualitative educational experiences helped her transcend the rigid traditional gender role division. With relevant skills and knowledge she was able to improve her own socio-economic position, but also the lives of many others. Now Nong Hom works on the social, economic and political issues of marginalised communities and in the future she aspires to give a voice to Burmese war victims who are often unheard in political processes. Nong Hom illustrates beautifully how qualitative education can empower women to become change-makers for themselves and the wider community.

When looking at the current state of education in Myanmar we can see how it is far from empowering. Statistics show gender parity in education and many argue Myanmar has met the MDG target of eliminating gender disparity in primary, secondary and tertiary education. But when we problematise these numbers, it shows much work is still to be done. School enrolment is high, but school is more accessible for the wealthier, ethnic majority. Besides the Bamar, who make up for roughly two thirds of the population, Myanmar is home to 135 other ethnic groups. Many ethnic minority groups live in the border areas, are internally displaced, fled to neighbouring countries and some groups, like Rohinya, are not recognised by the government and therefore excluded from provisions. For many ethnic groups access to education is difficult or impossible, but this is not reflected in statistics.

Furthermore, these numbers leave out one very important aspect; quality of education. In many cases the curriculum is a direct extension of government politics and therefore described by Nong Hom as ‘spoon-fed education’. According to her it creates ‘obedient citizens, while it should be about creating critical citizens’. Education that is about how well students can note, memorise and reproduce, without truly understanding, analysing and applying what has been taught in real life, will not break down social, political and economic structures which is crucial to work towards a democratic and inclusive society. For example, without questioning and redefining traditional gender roles in school settings existing rigid role models are perpetuated.

Besides a shift from students ‘as empty vessels that need to be filled’ to students as ‘co-creators of knowledge’, education needs to take into account gender specific needs. To overcome the gender gap several studies have pointed out that women from Myanmar need education not only for knowledge, but also for soft skills, like discussion and public participation, they do not acquire naturally in the course of their lives. Nong Hom, who studied in Myanmar and International Relations abroad at the Webster University, said: ‘International Relations is a challenging subject, but I don’t see it as something to overcome. If I don’t know how to do things, I learn how to do things and then I know how to do it. If you can adapt to a challenge, it is no longer a challenge.’ After graduating Nong Hom was able to bring back life skills like perseverance, reflexive attitude and improvisational skills, but maybe most importantly confidence, back to Myanmar. Now Nong Hom is making social change happen.

In the winds of change, the debates on education have flared up afresh also. The Parliament has been implementing educational reforms to ‘develop an education system that promotes a learning society capable of facing the challenges of the Knowledge Age that helps to build a modern developed nation’. In turn, student movements in Myanmar have demanded more drastic reforms for transparent, inclusive and grassroots education. In these dynamic and pressing times we should not forget women. How can education break down rigid role models and provide gender sensitive support to close the gap between men and women? Only when these questions are addressed education can be tool for achieving equality.

Author: Rianne Rietveld has a bachelor in Pedagogy and a Master in Social and Cultural Anthropology and is active in the fields of childhood, mental health and education. By giving a voice to vulnerable groups and analysing macro dynamics, Rianne tries to build bridges between local realities and the wider context.